Movie Sets

MOVIE SET APPLICATIONS BY WAAGMEESTER CANVAS PRODUCTS

“Can you rig up an old rope bridge for our movie set?”

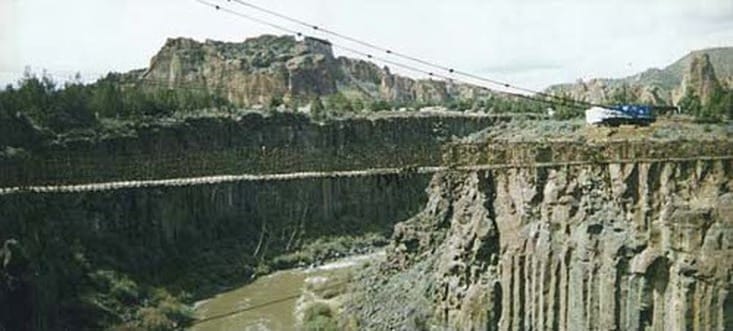

During the spring of 1997 Mr. Bob Blackburn, a set director for Warner Brothers, contacted us. They were shooting Kevin Costner’s movie, The Postman, in eastern Oregon around Bend and Smith Rocks. Warner Brothers was planning to rig a rope-sided suspension bridge across the Crooked River Gorge and wanted to know if we could make the rope sides for the bridge. The bridge would be 330 feet long.

In the 1940’s and 50’s cargo nets were still made out of rope, hand woven and spliced. I remembered my father making the nets in the back room of the shop a long time ago; but I didn’t recall the whole procedure. As the net was made, one or more horizontal rows at a time, it was lapped over the hooks and the finished part would grow into a pile on the floor behind. My mother recalls boiling salt water for my father and grandfather to soak their hands in to toughen up the skin, as the manila is very splintery. With the advent of nylon webbing a stronger and better cargo net could be made. The handwork was replaced by sewing machines. Our father was a Sail Makers Mate in the U.S. Navy and passed on rope work and sewing skills to his two sons. We had the basic skills to make this bridge but lacked the experience. Our shop had not made a rope cargo net in close to 50 years.

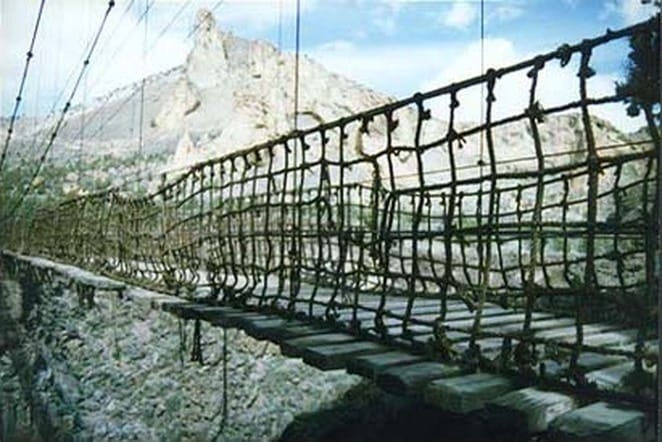

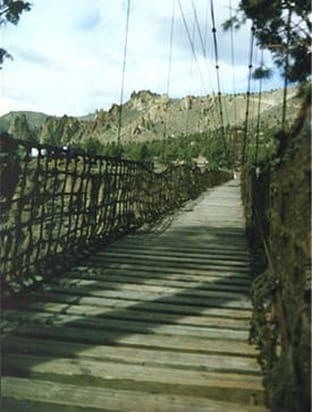

A number of sources were tapped for information as we started this project: former employees, the local Navy/Marine Reserve Center; and materials suppliers, however, the most help came from the Maritime Science Department of Clatsop Community College. Armed with our old skills and new confidence, we submitted our bid to Warner Brothers and got the job. One of our suppliers located the manila rope and the tarred marline that was needed for the job. In all we used 2,000 feet of 3/4″ and 12,000 feet of 1/2″ Manila rope and over 50 pounds of tarred Marline for the bridge sides. In 30 days time we made 880 lineal feet of net 3 1/2′ high with a 6″ mesh. All of our employees had some net time, we put in late nights and weekends until the job was complete. We also hired several part time employees to help with the project.

Some short cuts were used in order to save time and production money. The bitter end of the line is usually passed through the inner two strands of the border and then eye-spliced; the eye-splice involves tucking each of the three lays of the end through alternating lays for a total of nine tucks. Instead of eye-splicing each end of the horizontal and vertical lines to the border, the bitter end was passed through the border and then through one lay of itself and then wrapped with electricians tape. This saved much time since the net was attached to the border in over 3,400 places. There were also over 8,000 tucks in the net itself and over 4,000 seizings. The overall strength of the net was much weaker than if splices would have been used but the friction combination of the line going through itself and the border and being stretched tightly did an adequate job. We experimented and it held over 200 pounds on one splice without problems. The breaking strength of 1/2″ manila is 2,385 lbs. and 3/4″ is 5,750 lbs. The netting was used only for appearance as steel cables actually held the bridge together. I would have felt better splicing the ends but the movie people decided it wasn’t necessary.

The other major short cut was in the body of the net itself. The normal way of weaving a rope net is to alternate running a vertical through a horizontal and then the horizontal through a vertical; this way every other tuck is locked from sliding any further than the next tuck. Thus with a six inch mesh you can only open up a 12 inch hole. We took the short verticals and ran them through each of the five horizontals. Then every other tuck was seized with marline; this was an extra step, but it helped add to the ascetics of the bridge. The set people wanted the netting to look old and used. After the nets were delivered they were attacked with grinders and paints to simulate age and usage. We intentionally put in extra splicing and seizings to simulate patched and repaired areas. The seizings and splice ends were cut in varying lengths again to simulate wear and age. So the work of some relatively inexperienced net makers added to the ambiance of the movie and some archaic skills got passed on to a new generation.

Originally six 100 foot and two 30 foot nets were ordered. When these had been delivered two more 50 footers were ordered. They were for the stunt bridge which was to be built in a field only 15 feet above the ground. The 50 footers never saw the stunt bridge; one of the 100 footers turned up missing, so the two fifty footers went into the Crooked River Gorge bridge. Later two sixty footers were made for the stunt bridge. These we delivered to the stunt bridge site one day before filming. Our truck had barely stopped moving when the nets were on their way to be aged. The stunt bridge was in an open field. Actually the “bridge” was just a section of bridge corresponding to a section of the gorge bridge. The set crew assembled scaffolding around the bridge section. Later a green screen was to be draped around the scaffolding and the gorge scene would be digitized onto the film. This way some of the stunt scenes could be shot with much less risk to the actors. We also were taken to the gorge bridge and allowed to take pictures as long as we agreed not to publicize them until after the film was released. The security guards would not allow us on the bridge and didn’t like us taking pictures across the bridge. The set director intervened and we were allowed to take pictures but not allowed to cross it. The overall construction of the bridge was quite substantial; complete with concrete footings. It was about 4 feet wide; too bad it had to be destroyed after the film was made. Originally it was to be blown up, but I believe it was simply dismantled as there were environmental concerns about debris.

There were a number of homes in the immediate area of the bridge, these were camouflaged in a number of different ways. In some areas more trees and shrubs were temporarily planted. In others camouflage netting and walls of trees were used. By the time the nets were finished, two new generations had been exposed to some old skills. It was very nostalgic to again work with manila and marline and the tools that go with it: fids, marline spikes, knives, and needles. Many people complained about the smell, but I enjoyed the old, nearly forgotten aromas, as did some of our old customers. I had forgotten about the slivers one gets from marline and manila as well as the soothing effect the tar from the marline has on your hands.

It had been thirty years since I had done much rope work, but it’s like riding a bike, it came back quickly. I put in both long and short splices until they again came naturally. I put in a variety of eye-splices, remembering the way I was taught and the men who taught me; Swedish, Norwegian, and German sailors and riggers who once sailed on square rigged ships. I never knew my great grandfather who was an old square-rigger sailor, but he and my father used to put in late night sessions trying to out do each other in knot tying. My mother has told me how upset he used to become when he couldn’t remember how to tie a particular knot. There are hundreds of different splices, knots, bends, hitches, and fancywork that can be applied to three-strand rope. These were ways for the sailors to show their stuff, now a days, with the synthetic lines, you simply cut it with a hot knife or touch it to a match and it won’t unravel. On the old three-strand line, if it wasn’t knotted, seized, served, or whipped, it would unravel. Sailors would take any opportunity to show off their marlinespike skills. The way the yarns were twisted, tucked and trimmed would change the appearance of a knot or splice and would become the trademark of a particular person or ship. Marty, a German rigger, taught me his trade mark eye-splice. Fred showed me his way of sewing on rings and jib hanks. They were both very proud of their skills and enjoyed passing them on. Otto taught me different ways to sew rope on sails, merry-go-round covers, and awnings. A lot of these old skills and trademarks will never know another generation, but I guarantee that net making will last for several more.

Thanks for reading about this fun project we had. If you have a custom project that needs to be done, and it has anything to do with ropes, canvas, coverings, or cabling – we just might be up to the task. Give us a call or fire off a query by email – click here. – Steve Waagmeester.